Rocket Loader skimmer impersonates CloudFlare library in clever scheme

Posted: March 10, 2020 by Jérôme Segura

Last updated: March 11, 2020

Update: The digital certificate issued for https[.]ps has been revoked by GlobalSign.

Fraudsters are known for using social engineering tricks to dupe their victims, often times by impersonating authority figures to instill trust.

In a recent blog post, we noted how criminals behind Magecart skimmers mimicked content delivery networks in order to hide their payload. This time, we are looking at a far more clever scheme.

This latest skimmer is disguised as a JavaScript file that appears to be CloudFlare’s Rocket Loader, a library used to improve page load time. The attackers created an almost authentic replica by registering a specially crafted domain name.

This campaign has been affecting a number of e-commerce sites and shows threat actors will continue to come up with ingenious ways to deceive security analysts and website administrators alike.

Decoy Rocket Loader

On a compromised Magento site, we noticed that attackers had injected a script purporting to be the Rocket Loader library. In fact, we can see two almost identical versions loaded side by side.

If we look at their source code, we find that the two scripts are quite different. One of them is obfuscated, while the other is recognizable as the legitimate CloudFlare Rocket Loader library.

There is a subtle difference in the URI path loading both scripts. The malicious one uses a clever way to turn the domain name http.ps (note the dot ‘.’ , extra ‘p’ and double slash ‘//’) into something that looks like ‘https://’. The threat actors are taking advantage of the fact that since Google Chrome version 76, the “https” scheme (and special-case subdomain “www”) is no longer shown to users.

To reveal the full URL with its protocol, you can double click inside the address bar. In other browsers such as Firefox or Edge, the default is to show the entire URL. That makes this attack a little more obvious and therefore less effective if you were a site administrator investigating this library.

Active skimmer campaign

The Palestinian National Internet Naming Authority (PNINA) is the official domain registry for the .ps country code Top-Level-Domain (ccTLD). The decoy domain http.ps was registered on 2020-02-07 via the Key-Systems GmbH registrar.

In mid-February, security researcher Willem de Groot tweeted about how this domain was being used for credit card skimming in an ongoing campaign with the additional “e4[.]ms” domain.

The skimmer code as well as its exfiltration gate (autocapital[.]pw), were described by Denis Sinegubko, a security researcher at GoDaddy/Sucuri.

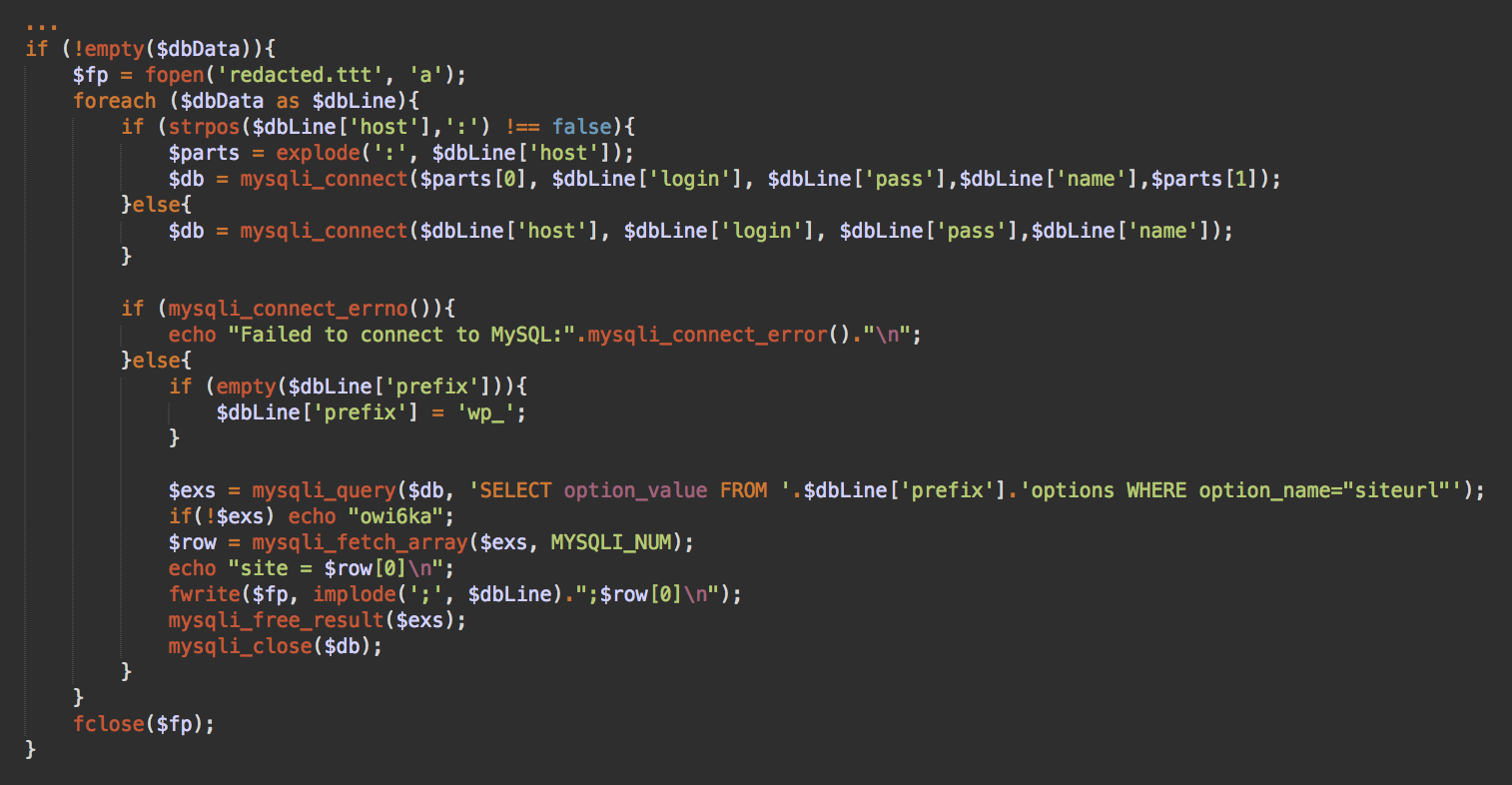

There are two ways e-commerce sites are being compromised:

Skimming code that is injected into a self hosted JavaScript library (the jQuery library seems to be the most targeted)

A script that references an external JavaScript, hosted on a malicious site

The first version of the skimmer used in this campaign is the hex obfuscated type with data exfiltration via autocapital[.]pw as seen in the decoy Rocket Loader library. As Denis mentioned in his tweet, this skimmer contains an English and Portuguese version (urlscan.io archive here).

The other version of the skimmer (hosted on e4[.]ms) uses a different obfuscation scheme with data exfiltration via xxx-club[.]pw (this domain is on the same server as the autocapital[.]pw exfiltration gate).

We recognize this obfuscation pattern as ‘Radix’, from a previous campaign described and tracked by Sucuri since 2016. Given the naming convention used for the domains and skimmers, we believe the same threat actors may be behind this newest wave of attacks.

Patching and proactive security

This kind of attack reinforces the importance of good website security. The majority of compromises happen on sites that have not been updated or that use weak login credentials. These days, other forms of defense include web application firewalls and general hardening of the CMS and its server.

The majority of consumers that shop on a compromised site will have no idea that something went wrong until it’s too late. Even though it is the responsibility of the merchant to ensure their platform is secure, it is obvious that additional containment needs to be taken by visitors themselves.

Malwarebytes users are protected against this credit card skimming attack via our web protection layer in Malwarebytes for consumers and businesses.

We have reached out to the registrar and certificate authority but at the time of writing the malicious decoy domain is still active.

Indicators of compromise

Skimmers and gateshttp[.]ps autocapital[.]pw xxx-club[.]pw e4[.]ms y5[.]ms

83.166.248[.]67

83.166.244[.]189

4×4 grid of memory cells representing a DRAM chip

4×4 grid of memory cells representing a DRAM chip

The WHO says it is okay to receive packages delivered from China.

The WHO says it is okay to receive packages delivered from China. A screenshot of an emailed coronavirus scam that preys on users’ good will.

A screenshot of an emailed coronavirus scam that preys on users’ good will. A screenshot of the emailed coronavirus scam that Sophos discovered.

A screenshot of the emailed coronavirus scam that Sophos discovered.