We regularly talk about brute force attacks on WordPress sites and explain why WordPress credentials should always be unique, complex, and hard to guess.

However, the WordPress login is not the only point of entry that hackers use to break into sites. Since the WordPress CMS stores most of its settings in a database, attackers can get access directly to the database to modify functionality and inject malicious code.

Brute Force Attacks on WordPress Databases

Databases are another potential target for brute force attacks. Hosting providers usually prevent access from external networks to their own database servers to minimize the risks of unwanted connections. That being said, usually hundreds — or even thousands — of websites connect to the same database server, so hackers just need to compromise a single site to start a database brute force attack from an internal IP.

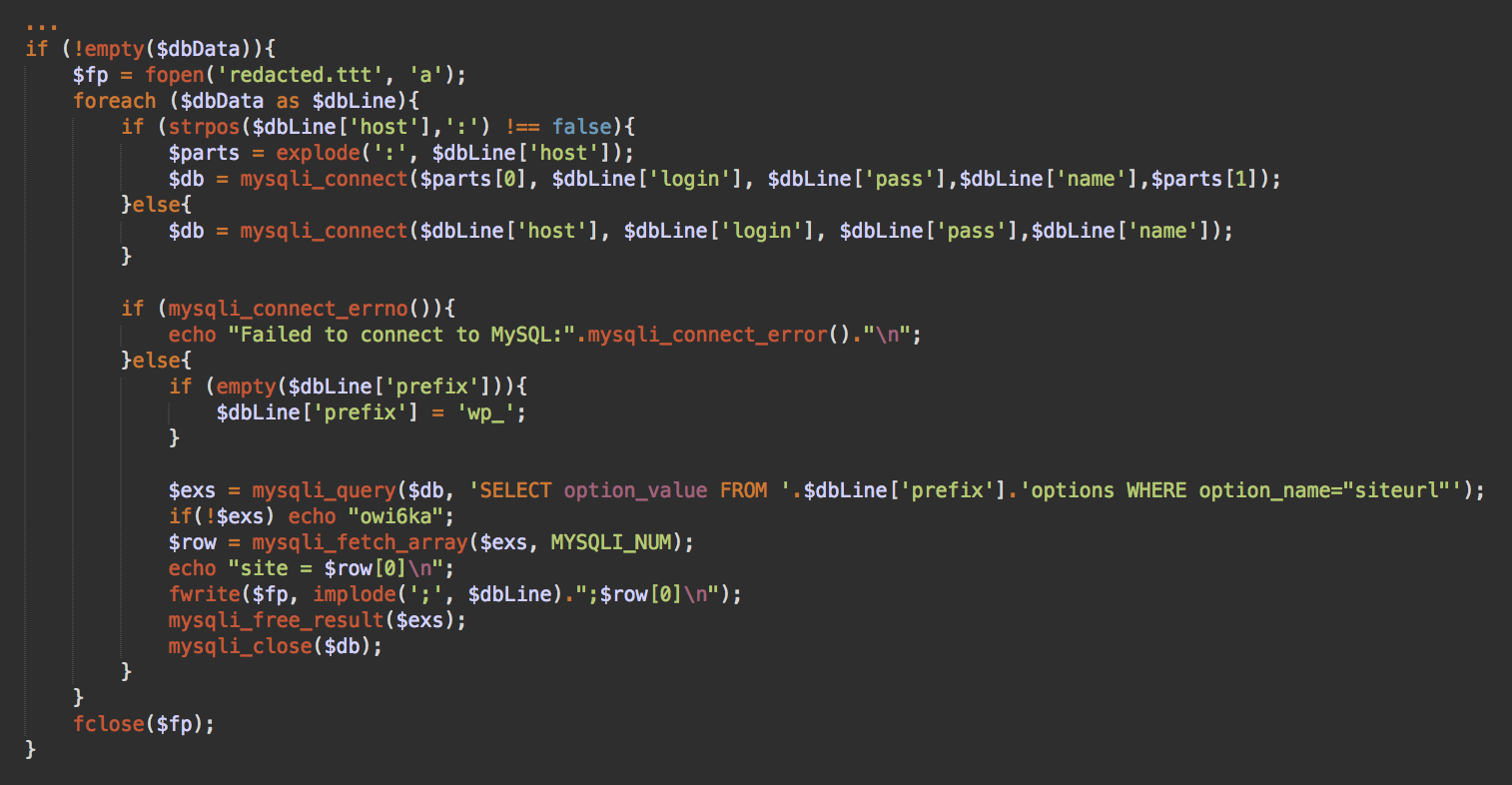

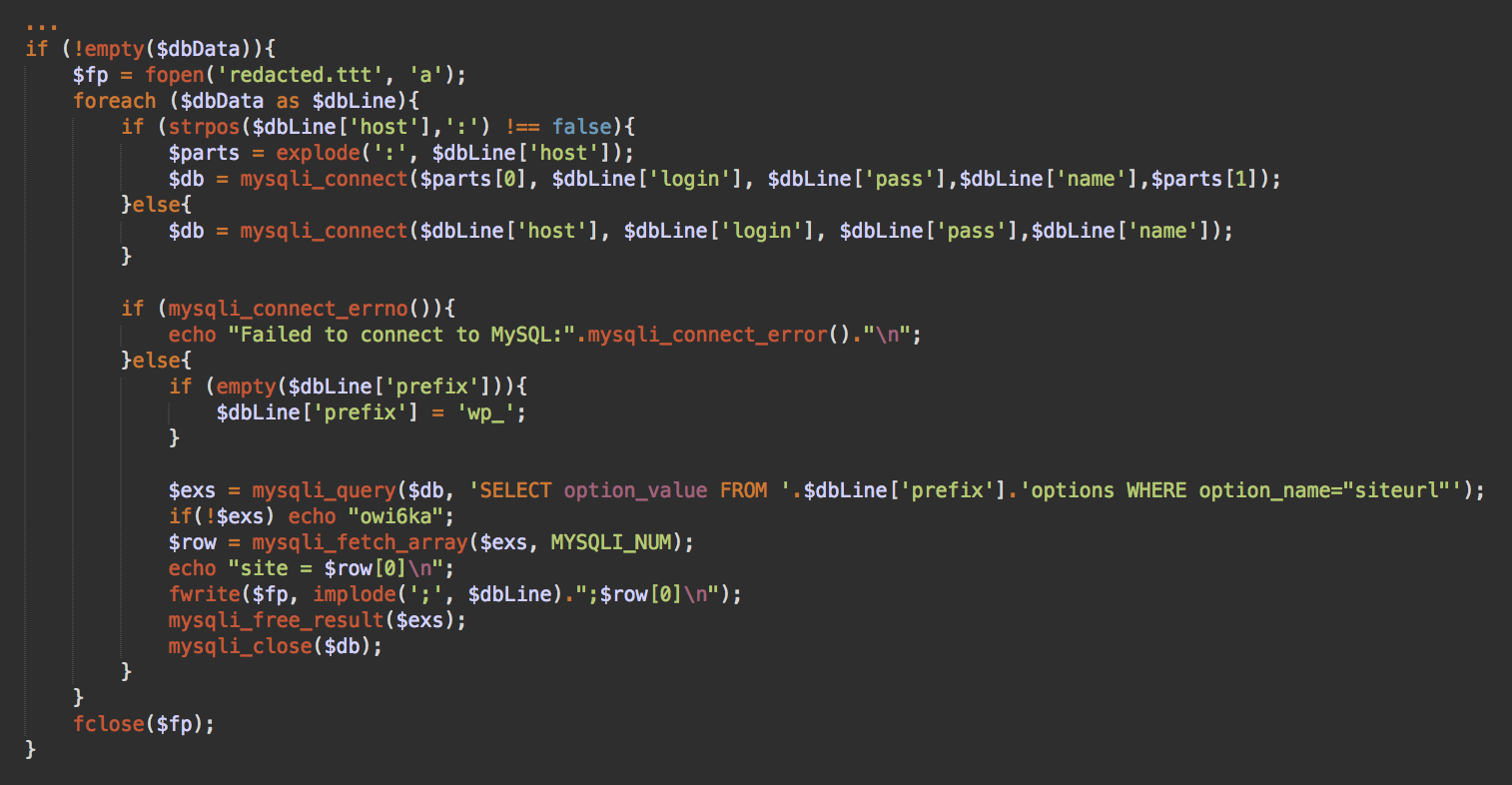

For example, one database brute force script we recently found (base.php) loads multiple database credentials from .txt files.

DB_NAME

DB_USER

DB_PASSWORD

DB_HOST

table_prefix

The script then tries to use these credentials to connect to the database. If a connection is established, they try to obtain the siteurl option from the WordPress wp_options table, which helps the attacker identify which site the matched credentials belong to.

Interesting note: This script prints “owi6ka” if it can’t query the siteurl from the database. This word uses Latin gomoglyths to represent the Russian word “ошибка” (error).

Feasibility of Database Brute Force Attacks

Of course, this approach to brute forcing database credentials may seem significantly more difficult since the attacker is required to guess five connection parameters instead of just two. It’s worth noting that most reputable hosting providers implement proper configuration and assign randomized database names, which mitigates the risk of this type of attack. However, when hosting providers don’t follow security best practices, the approach may still be worthwhile — as demonstrated below.

For example, if you compromise one site on a shared server, you get the host name of the database that is shared by many other sites. Lots of sites use the default “wp_” table prefix. This leaves us with three more parameters to guess.

If the hosting provider has a known pattern of naming databases and database users, then the patterns can be used to generate credentials to probe. All of these prerequisites significantly reduce the difficulty level of guessing database credentials. And given that the attack can’t be blocked by plugins or HTTP-level firewalls and comes from an internal network, this attack approach can try lots of combinations without much interference.

Of course, this is only possible if the database server firewall is not configured to block excessive failed logins — and setting this up can be tricky, since you can’t block an internal IP address that is shared by hundreds of other client sites that rely on the database every second.

Alternative Use Scenarios

This malicious brute force script can be also used in the following scenarios:

If a server’s accounts are not properly isolated and the attacker is able to obtain access to even a single website, it becomes possible to obtain read access to wp-config.php files from other sites and accounts on the same shared server. Credentials from these files can be used by this script to connect to the databases of neighboring sites and find out their addresses.

Another scenario arises when hackers break into a site and want to maintain access to it. The main way to accomplish this is to plant various backdoor scripts and create rogue admin users. However, both of these solutions can be detected and removed during a site cleanup. On the other hand, if hackers successfully guess or steal the credentials of a legitimate admin user, they can also reuse them indefinitely. That’s why we strongly encourage website owners to change all of their passwords after every site compromise.

While many site owners change CMS passwords, however, very few of them ever change their database passwords. So, if hackers steal the database credentials, they leave no traces on the compromised site but still can access it (usually from other compromised sites on the same shared environment).

This script we discovered could easily help them manage the list of the stolen credentials and verify which of them are still valid.

Conclusion

While database brute force attacks are not seen often in the wild, there is definitely some interest in alternative attack vectors.

Ensuring that hosts properly configure their shared server environments may significantly mitigate risks to client websites. User accounts should be completely isolated so that CMS configuration files cannot be read by neighbors. Hosts should assign hard to guess database names and database user names. When installing WordPress, webmasters should also be creative when choosing prefix for WordPress database.

When a CMS website has been compromised, you can bet that hackers aren’t just planting backdoors and malicious code on the site. There’s a less-obvious aspect to a compromise that some users may not consider: attackers will also be on the lookout for password and database credentials found in CMS configuration files, such as wp-config — and it’s virtually impossible to detect if an attacker has gathered these at any stage of the infection.

If a compromise occurs, you should be vigilant in updating passwords across your entire environment — including the database. If you don’t change the database credentials after cleanup, hackers may still have access and be able to modify your site via compromised neighbor accounts on the same host, which is not that uncommon in shared hosting environments.

Site owners can refer to our website security guide on best practices and other ways to mitigate risk. If you believe your WordPress website or database has been hacked, we can help clean up the website infection and secure your environment from future compromise.

The script then tries to use these credentials to connect to the database. If a connection is established, they try to obtain the siteurl option from the WordPress wp_options table, which helps the attacker identify which site the matched credentials belong to.

Interesting note: This script prints “owi6ka” if it can’t query the siteurl from the database. This word uses Latin gomoglyths to represent the Russian word “ошибка” (error).

Feasibility of Database Brute Force Attacks

Of course, this approach to brute forcing database credentials may seem significantly more difficult since the attacker is required to guess five connection parameters instead of just two. It’s worth noting that most reputable hosting providers implement proper configuration and assign randomized database names, which mitigates the risk of this type of attack. However, when hosting providers don’t follow security best practices, the approach may still be worthwhile — as demonstrated below.

For example, if you compromise one site on a shared server, you get the host name of the database that is shared by many other sites. Lots of sites use the default “wp_” table prefix. This leaves us with three more parameters to guess.

If the hosting provider has a known pattern of naming databases and database users, then the patterns can be used to generate credentials to probe. All of these prerequisites significantly reduce the difficulty level of guessing database credentials. And given that the attack can’t be blocked by plugins or HTTP-level firewalls and comes from an internal network, this attack approach can try lots of combinations without much interference.

Of course, this is only possible if the database server firewall is not configured to block excessive failed logins — and setting this up can be tricky, since you can’t block an internal IP address that is shared by hundreds of other client sites that rely on the database every second.

Alternative Use Scenarios

This malicious brute force script can be also used in the following scenarios:

If a server’s accounts are not properly isolated and the attacker is able to obtain access to even a single website, it becomes possible to obtain read access to wp-config.php files from other sites and accounts on the same shared server. Credentials from these files can be used by this script to connect to the databases of neighboring sites and find out their addresses.

Another scenario arises when hackers break into a site and want to maintain access to it. The main way to accomplish this is to plant various backdoor scripts and create rogue admin users. However, both of these solutions can be detected and removed during a site cleanup. On the other hand, if hackers successfully guess or steal the credentials of a legitimate admin user, they can also reuse them indefinitely. That’s why we strongly encourage website owners to change all of their passwords after every site compromise.

While many site owners change CMS passwords, however, very few of them ever change their database passwords. So, if hackers steal the database credentials, they leave no traces on the compromised site but still can access it (usually from other compromised sites on the same shared environment).

This script we discovered could easily help them manage the list of the stolen credentials and verify which of them are still valid.

Conclusion

While database brute force attacks are not seen often in the wild, there is definitely some interest in alternative attack vectors.

Ensuring that hosts properly configure their shared server environments may significantly mitigate risks to client websites. User accounts should be completely isolated so that CMS configuration files cannot be read by neighbors. Hosts should assign hard to guess database names and database user names. When installing WordPress, webmasters should also be creative when choosing prefix for WordPress database.

When a CMS website has been compromised, you can bet that hackers aren’t just planting backdoors and malicious code on the site. There’s a less-obvious aspect to a compromise that some users may not consider: attackers will also be on the lookout for password and database credentials found in CMS configuration files, such as wp-config — and it’s virtually impossible to detect if an attacker has gathered these at any stage of the infection.

If a compromise occurs, you should be vigilant in updating passwords across your entire environment — including the database. If you don’t change the database credentials after cleanup, hackers may still have access and be able to modify your site via compromised neighbor accounts on the same host, which is not that uncommon in shared hosting environments.

Site owners can refer to our website security guide on best practices and other ways to mitigate risk. If you believe your WordPress website or database has been hacked, we can help clean up the website infection and secure your environment from future compromise.

No comments:

Post a Comment